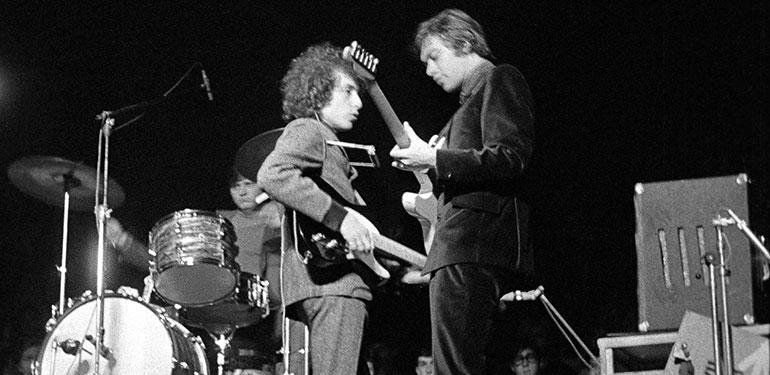

On 17 May the 50th anniversary of Bob Dylan ‘going electric’ at the Manchester Free Trade Hall is set to be marked by the Electric 50 gig at Manchester Academy. CP Lee – a member of Manchester District Music Archive and author of Like The Night – has written us a guest column recalling that fateful night (while the picture above was taken by Mark Makin, who attended the show while still a school boy).

As soon as word got to me that Bob Dylan would be appearing at the Free Trade Hall, I went home and announced to my mum that I would be going to see him and I would need to borrow one pound to buy a ticket at Hime and Addison’s on John Dalton Street. It cost me the grand sum, including a booking fee, of 13s 3d. School couldn’t finish quickly enough on Tuesday, 17 May 1966 and I rushed to the gig straight after the bell rang.

A friend and I stood around the back of the Free Trade Hall on the misapprehension that Dylan would be waiting there so we could meet him – he wasn’t. So, I went home and got changed into my black jacket, jeans and my button-down shirt, I had my tea fast as I could and went straight back to town on the bus.

At 7pm, I was stood on my own in the queue outside with about two thousand other people. Conversation crackled about Dylan’s reception in Ireland the week before, NME and Melody Maker reporting how Dylan had been booed when he came on with his backing band, the gigs becoming tense and confrontational. It was unsettling; with the Manchester Evening News also speculating whether there would be some kind of trouble at the concert. Once inside, I could hear heated conversations and arguments for and against an ‘electric’ Dylan.

Just after 7.30pm, we were in and the house lights dimmed and a sepulchral hush fell on the Hall. Lit by a single spotlight, I was thrilled to see the diminutive figure of Dylan, carrying an acoustic guitar and with a harmonica strapped round his neck enter from side stage to rapturous applause. Some people appeared to be sighing in relief that he was performing solo, the tension dissipating to a hushed, reverential atmosphere. But, nobody could have failed to see an organ, grand piano, amplifiers and a drum kit on stage. It seemed fairly obvious that he wasn’t going to remain alone; he was going to use a band! But not yet.

Dylan played his forty-five minute set consisting of some old standards like She Belongs To Me and Mister Tambourine Man, but new numbers kept appearing that were a complete mystery to us being prior to their appearance on the Blonde On Blonde album which Dylan had recorded (with backing) in Nashville a few months before. All too soon the first half ended and, as Dylan bowed and left the stage for the intermission, the crowd breathed a sigh of satisfaction. Any confrontation that might have taken place in Manchester now seemed to have been defused and people were overheard saying that Dylan had ‘seen sense’.

After the break, Dylan returned – he was with the group who would become known as The Band. Dylan launched loudly into his second set and – I’m not the only one to say this – it felt like I was being pushed back in my seat as when a jet liner takes off.

After the first number there was polite applause. Really, the reaction was more one of stunned vacancy. It was hard to take it all in. I’d never heard Tell Me Mamma and I couldn’t even hear the words clearly over the sheer power and volume which was quite overwhelming. The acoustics in the Victorian hall weren’t up the sound, which was raw and visceral. The official Bootleg Series release Live At The Albert Hall (recorded that night in Manchester) is a cleaned-up reproduction of what we heard that night. Dylan took no prisoners.

The deniers slowly started to react, some starting slow handicapping between songs. Perhaps partly due to Dylan’s inordinate use of time between songs, tuning and walking around the stage. He didn’t speak. He just let the atmosphere hang while the tension built up. However, after more slow handclaps the fissures started to open and he could be heard mumbling like an old fairground barker, they saying into the microphone: “If only you wouldn’t clap so hard”.

After Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, a young woman came up to the stage and handed Dylan a note. Dylan read it, blew her a kiss and put the note in his pocket. It wasn’t until thirty years later that the woman, Barbara, revealed that the note had said: “Send the band back home”. Interviewed for my book, Like The Night, she admitted her later embarrassment.

Leopard-Skin Pillbox Hat had me transfixed, the sound reverberating through my entire body. I felt I was walking with gods. Again, once the sound had died down, came slow handclapping and the first, loud catcalls and booing. Groups of people stood up and walked out; pointedly staring at the stage to ensure Dylan knew they were ‘protesting’. The vibe in the hall was now fractious and squabbles had begun to break out between ‘Modernists’ and ‘Traditionalists’. Luckily for me, the people on my row seemed to be enjoying the show, but for others it was all getting a bit too much. A friend of mine, who was then just an innocent 15 year-old, felt such anger at the booing that he bravely took issue with the bigger, meaner adults around him.

Then, after the penultimate number, Ballad of a Thin Man, came the shout. A single, loud heckle…

“JUDAS!”

Being sat in the stalls underneath I could hear a shout but not the word, but looking at Dylan’s face I could see the significance. On reflection, it took an age for Dylan to respond.

“I don’t believe you. You’re a liar.”

Then Dylan smashed into a version of his Top Ten hit, Like A Rolling Stone, which ploughed like a relentless juggernaut into the folky opposition and, by this pure electric version, pop became rock. To me, it said: “This is it. This is what I do – Dig it or split”, which is what Dylan did the moment the number ended. Bowing politely, Dylan said a brief “Thank you” and, like the night, was gone.

As the tin-pot PA system rattled out the national anthem it was clear that it was all over. An air of shocked bewilderment hung in the air, like a cloud of mustard gas. Leaving behind a gang of protestors, still hanging around in the lobby, I ran off to catch the last bus knowing that the music from that concert would be implanted forever in my memory and somehow instinctively knew I’d been present at something remarkable.

CP Lee@MDMArchive

For more head to Mdmarchive.co.uk.

Picture: © Mark Makin